Pathankot City

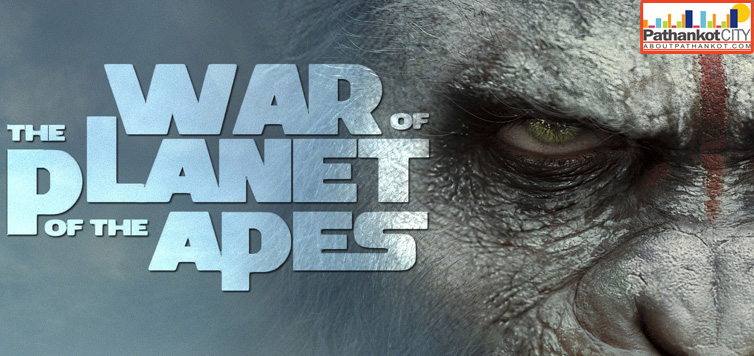

War for the Planet of the Apes Movie Pathankot PVR Cinemas Timings Book Tickets

Show Timings in PVR (Hindi): 10:00 13:00 16:00 22:00

Show Timings in PVR (Hindi): 19:00

Book Tickets Now

Official Trailer

An action-oriented sci-fi film directed by Matt Reeves, starring Andy Serkis, Judy Greer and Woody Harrelson in the lead roles.

Is War of the Planet of the Apes the greatest Biblical epic ever made?

I’m half-kidding. It’s a movie about talking apes, after all, led by a chimpanzee named Caesar, and it’s set in a post-apocalyptic future America, where Woody Harrelson is running a rogue paramilitary force. None of those things appear in the Holy Writ.

But then again, that paramilitary force rallies beneath a tattered American flag spray-painted with the call sign ΑΩ — Alpha Omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet and a name used for God in the Biblical book of Revelation. They force captive apes into servitude in a manner that recalls images of the enslaved Israelites in Egypt being forced to build pyramids. Several scenes — including the final one — clearly paint Caesar, leader of the apes, as a Moses figure.

Rating

And though this last installment in the excellent contemporary Apes trilogy (preceded by 2011’s Rise and 2014’s Dawn) isn’t a direct Bible story retelling, it incorporates elements that echo the Bible, and leans hard on the Biblical epic’s hallmarks, too: vast and ancient-feeling stories of oppression, betrayal, and triumph, mixed with small moments of human drama.

War for the Planet of the Apes is a better Biblical epic than most recent Biblical epics

That the movie evokes a Biblical epic so successfully is significant all on its own. Though the form flourished in Hollywood’s Golden Age — when a studio might be willing to spend enormous amounts of money on lavish productions that nearly bankrupted the studio — a more recent wave of Bible movies that popped up a decade after the runaway success of Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ haven’t been quite as successful.

In 2014, Son of God made plenty of money at the box office by studiously avoiding any artistic liberties that would offend the risk-averse “faith-based” audience, which loudly protested the more adventurous Noah earlier the same year. Meanwhile, Exodus: Gods and Kings (protested partly for its whitewashed casting) fell flat with critics and audiences, as did a remake of Ben-Hur two years later

War for the Planet of the Apes, having decoupled itself from the obligation to be faithful to any holy text in particular, is able to do all kinds of things recent Biblical blockbusters couldn’t pull off. It can reference other kinds of movies and other genres. It can layer symbols and code into its characters and settings to evoke several historical narratives at once. It can crack jokes and stage breathtaking action scenes and imagine narrative twists, with no purists coming after them with lit torches crying foul (except bonobo purists).

But it still makes clear choices that emulate Biblical epics — something director Matt Reeves told Entertainment Weekly was intentional.

“We watched Bridge on the River Kwai,” Reeves told the magazine. “We watched The Great Escape. We watched Biblical epics, because I really felt like this movie had to have a Biblical aspect to it. We watched Ben-Hur, The Ten Commandments … When you surround yourself with something that feels emotionally right, there are connections that make sense to you that somebody else might not see.” Those films, Reeves said, informed War’s “vibe.”

The result of this is a remarkably rich and complex blockbuster — much more than most people expect from a movie starring CGI apes, one of whom sports a puffer vest. And it’s entertaining, too.

War for the Planet of the Apes is the rare blockbuster that’s both entertaining and full of complexity

To recognize how much of an achievement this is, you only need to look back at the ambitious, muddled mess that was Alien: Covenant, another blockbuster prequel with an ostensibly steady hand on the wheel (Ridley Scott’s) that fell apart because it just couldn’t figure out what it was about. Was it about Satan? Evolved consciousness? The conflict between faith and science? The fall of man? We don’t know, because the movie doesn’t know, either.

Unlike Alien: Covenant, though, War for the Planet of the Apes knows exactly what it’s after. You could say the film is about what makes us human, except using that species-specific word isn’t quite right. Really, it’s more about what makes living beings worthy of saving — that is, it asks what a soul is, and who has one, and what beings with souls owe to one another. Near the end of the previous installment, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, Caesar declared that the rebel ape Koba wasn’t an ape, which seemed to make tossing him over a ledge to his death more acceptable in the face of the “ape not kill ape” dictum ruling the apes’ civilization.

That might seem to tie a being’s fitness to live to their level of empathy or compassion for others, an addition to the idea in all three films that language plays an important role in separating “human” from animal.

But War for the Planet of the Apes extends this idea by delving into something more: the nature of the soul. That’s no small task for a summer blockbuster.

War for the Planet of the Apes has a complex view of human — and ape — nature

The two Apes films that came before War tried to imagine a world where primate species might coexist alongside one another. But watching them, there’s an inescapable sense of doom, as telegraphed right there in the title: Only one species will win out, and it has to do so in this movie.

But War for the Planet of the Apes is careful to nuance this inevitability in its universe with two caveats. The apes have to win eventually — these are prequel films to 1974’s Planet of the Apes, after all — but the reason has less to do with their superior nature and more with the idea that human nature is too faulty and degraded to share its spot at the top of the food chain with anyone else. If pride is humanity’s original sin, then pride is also what takes humanity down.

But just because someone is an ape doesn’t make them automatically “good,” or even more “civilized.” To take that path would have skirted dangerously close to a sort of patronizing “noble savage” fallacy, where a whole class of “human” is deemed too simple to imagine wickedness or bear moral culpability, instead living in a naive Edenic state. That’s not the apes. They’ve developed natures and civilizations as morally complex and advanced as the homo sapiens’.

In the Apes universe, both ape and man have complex natures that force the responsibility for choosing to be good or wicked onto the creature themselves. The film is careful to paint a world where apes have to make choices, and humans do, too. What seems to have changed in the apes as they gained the power of speech isn’t so much the ability to form complex thoughts as to make moral choices. And while theologians and philosophers debate whether things called souls exist and what their nature is, the idea of the soul — part of a being that can be saved or damned, formed toward good ends or evil ones — is at the root of how Apes thinks about what it is to be a sentient, morally culpable being.

When War for the Planet of the Apes begins, the battle for the planet is in full swing

War for the Planet of the Apes picks up, then, where Dawn left off, a few years out: Most of human civilization has been wiped out by the simian flu, and those who remain are mostly soldiers and military who have banded together to protect what’s left of humanity. In the previous film, Koba managed to start a war with the humans, and now Caesar has to reluctantly finish it.

The film looks like a war film, because it is, with tracking shots that recall films like Platoon and self-conscious references to Apocalypse Now (including a quip — “APE-POCALYPSE NOW” — scrawled on the side of a cave). The apes are hiding out after a bloody battle in which they exterminate all but four humans, whom they send home to their leader as a message.

Following that incident, Caesar’s elder son returns from a long scouting trip with news of a land across the desert where the apes can live in peace. (This is a clear callback to the moment in the Biblical book of Numbers when Joshua — Moses’ protégée and de facto son — and another man, Caleb, return with news of the Promised Land, a place “flowing with milk and honey.”) The apes make plans to leave for safety.

But they’re ambushed in the middle of the night, resulting in a bloody, heartbreaking loss for Caesar, thanks to a ruthless human colonel (Woody Harrelson). While he sends the rest of the tribe off to safety, including his tiny son, Caesar and three loyal apes who won’t leave him (including lovable orangutan Maurice) take off to find and kill the colonel. The journey that follows leads them through several discoveries — including stumbling across a little girl (Amiah Miller) who doesn’t seem to be able to speak, and Bad Ape (Steve Zahn), who’s both the movie’s comic relief and actually a very good ape.

War for the Planet of the Apes evokes at least four different historical periods of oppression

But when Caesar finally finds the colonel, the film tilts into full metaphorical mode. It evokes not just the children of Israel in Egyptian enslavement but also movements that have used that story as inspiration for their own struggle for freedom during the American Civil War and the Civil Rights movement. It also consciously calls to mind the Holocaust, with homages to The Great Escape and soldiers styled to look like both Nazis and white-supremacist militants.

All of those references piled onto one another have a larger effect that’s both damning and cautionary. Humans from almost the dawn of history have sought to dehumanize and delegitimize whole classes of people in order to oppress and destroy them. In a post-apocalyptic future, it’s no different — apes can gain the power of speech and reasoning and still be scorned by the very humans whose civilization is obviously dying out. And even when Caesar discovers the real reason that the colonel and his soldiers have gone rogue, it’s clear that the humans’ motive isn’t really how to best survive, but how to maintain the purity of their kind.

Harrelson is a perfect fit for his role, terrifying and tortured at once, but in War for the Planet of the Apes he can’t hold a candle to Andy Serkis, playing Caesar beneath layers of truly remarkable CGI. If you’re tempted to think most of the work happens in the CGI, it’s worth watching video of Serkis’s performance and transformation to realize that he’s giving an award-worthy performance. Serkis has to embody characteristics of both a chimp and a human, and the result is one of the great epic characters in cinema. Give this man an Oscar.

War for the Planet of the Apes echoes the Bible in its conclusion, and thus sets itself up for a sequel

The end of War for the Planet of the Apes clearly echoes Deuteronomy 34, in which Moses, having freed the children of Israel from bondage in Egypt and led them through 40 years of wandering in the wilderness, finally reaches the Promised Land. Due to an episode of anger and disobedience years earlier, though, Moses isn’t permitted to enter the land. God just shows it to him before he dies. It’s his protégée, Joshua, who takes over.

But Moses’s place in history is secured nonetheless; “No one has ever shown the mighty power or performed the awesome deeds that Moses did in the sight of all Israel,” the book of Deuteronomy records before it moves into accounts of great conquests and triumphs. That War for the Planet of the Apes echoes this account so clearly is a good indication of what could happen next, should more films be made in that genre.

Bad Ape in War for the Planet of the Apes

And yet, even if nothing follows this film, War for the Planet of the Apes is an achievement that’s especially welcome in a blockbuster landscape dotted by superheroes, reboots, and flat, unimaginative sequels. It has something to say, and says it with a cinematic sensibility that’s uncommon in most movies, let alone big-budget epics.

And what it wants to say is a warning for us, specifically, in an age where everyone from our political opponents to the world’s refugees are categorized, shoved aside, demonized, and dehumanized. The responsibility that comes with having a soul — or however you prefer to conceive of moral culpability — is to not just our own kind but our neighbor. The Apes universe isn’t our own, just yet.

War for the Planet of the Apes opens in theaters on July 14.

SOURCE: goo.gl/5ebuxL

Copyright © 2024 About Pathankot | Website by RankSmartz ( )

)

Fantastic hollywood movie and story is oooooosome…..